Think about how a friend told you a story about the last time they were late. They picked the important moments that established a cause and effect that led to them standing you up. ‘First I spilled coffee on the floor. I had to go to the store to buy more carpet cleaner. But it wasn’t open yet, so I had to wait and by the time I got back and cleaned it up I’d missed the train to get me here on time.’

Writers do the same thing: we cherry-pick certain moments that link cause and effect from beginning to end, leaving out the unimportant moments that don’t fit into this chain of consequences. But how do we choose which moments go into a story?

Narrative structure is how we make sense of the world and fundamental to stories. It provides methods for choosing what to include and what to leave out to make the story something meaningful and understandable to our reader, who can see how events are connected, and know what to pay attention to.

This post will provide an overview of the most popular story structures, and how these various structures are relevant to novel-length manuscripts. I have used predominately popular movie examples because it’s more likely that you’ll be familiar with the story, even if you haven’t seen the film.

Three Act Structure

Three Act Structure is arguably the most famous, and many other structures fall inside it. Aristotle described (perhaps unhelpfully to us) that stories must have a Beginning, Middle and an End. Let’s break it down and see how it can be used when writing a manuscript.

WHAT’S CONTAINED IN A THREE ACT STRUCTURE

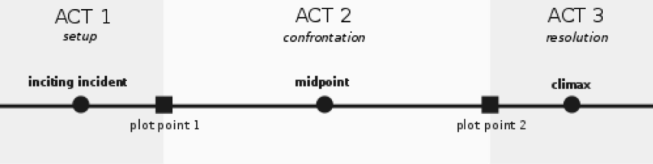

source: Puikstekend via Wikicommons

Each Act is loosely defined by the focus of the tension of that sequence: The Will they/ Won’t they? Question. E.g. For ‘Mad Max: Fury Road’ it can be the following:

- Act: 1 Will they outrun those chasing them?

- Act: 2 Will they find the Green Place?

- Act 3: Will they defeat the main villain, Immortan Joe?

Act 1 is usually the first quarter of the story. It introduces the characters, the world and their problem. The inciting incident often occurs about halfway through this act and is the moment that kicks off the story. For example: When Furiosa steals the truck to help the women escape.

The first plot point is often a major decision made by the character and indicates the start of Act 2. This is the point where the reader sees there is no going back to the safe world of Act 1. Max decides to team up with Furiosa and the women.

Halfway through Act 2 is the midpoint. This is usually a disaster which throws everything upside down for the character. Furiosa learns there is no Green Place. The character then must learn to rebuild themselves. Act 2 ends on the next major plot point, which is another moment where the character’s world seems about to be upended again.

Act 3 has the climax; that inevitable moment the story has been heading toward right from the start, and then the resolution of how the character lives with their new, hard-won knowledge. It’s not enough to free themselves, Furiosa and the women must free everybody from Immortan Joe’s dictatorship.

Three Act Structure is inescapable because it’s fundamental to how we learn. It is always about a character encountering something new (the inciting incident), their struggle to understand it (plot point 1), their different attempts (Act 2) and then their overall knowledge expanding to encompass it (climax). Finally, that knowledge becomes part of their greater understanding and the character grows as a result.

This also describes exactly how we learn any new skill. For example, a gymnast learns a new technique, works on perfecting this technique, then adds it to their routine.

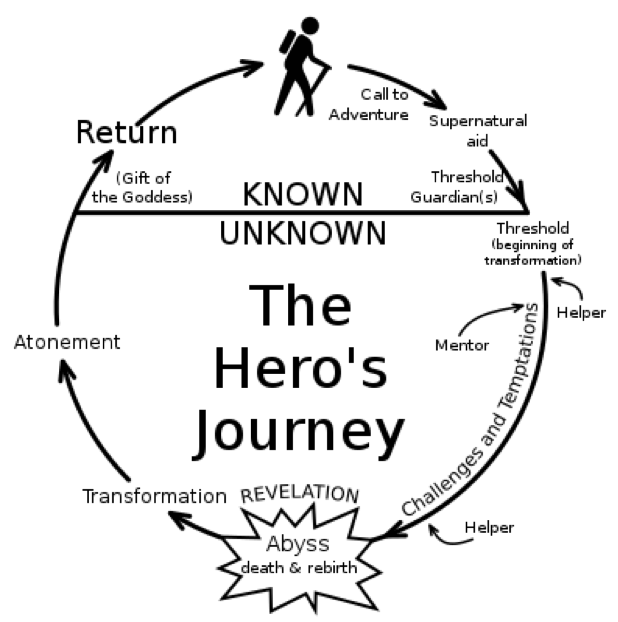

Contained neatly within a three Act Structure is The Hero’s Journey by Joseph Campbell

Joseph Campbell argued for the idea of the ‘Monomyth’: where all hero stories follow the same broad template. The hero goes on a journey that culminates in some sort of crisis, followed by a decisive victory. The hero ends the story changed by the experience. Later theorists and writers have added on to Campbell’s work, making new plot points but their essence is usually the same.

source: WikiCommons

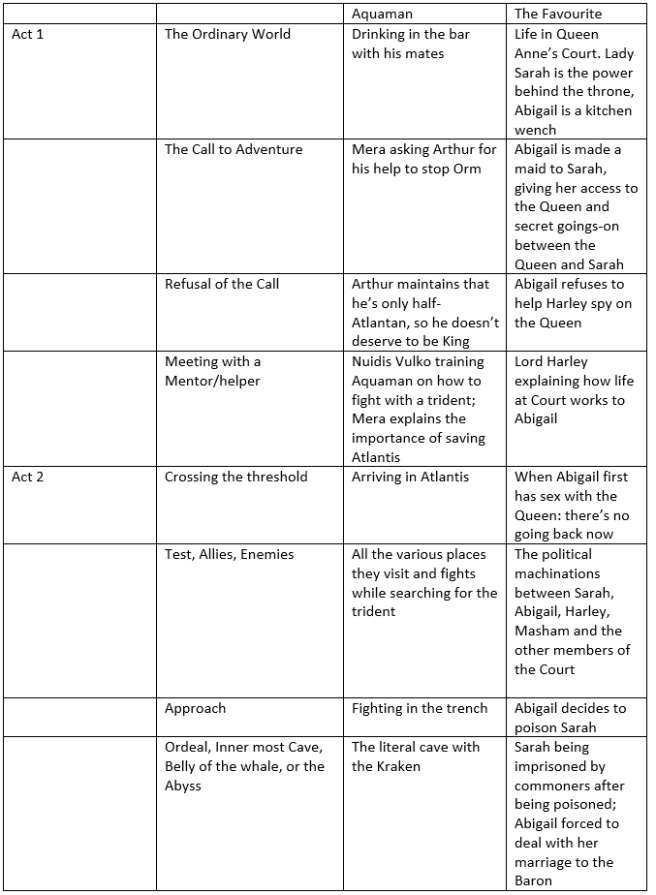

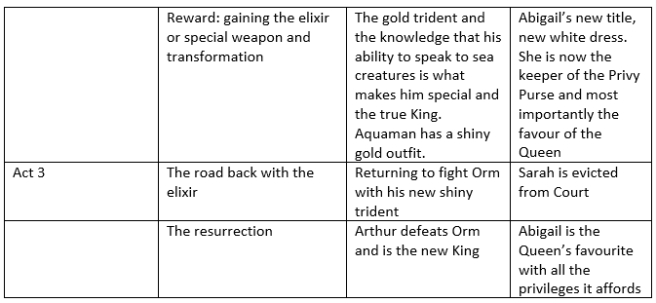

The Hero’s Journey isn’t just for a fantasy where there is a literal hero. It can be applied to almost any type of story. Below, I’ve mapped two very different recent films to show how this can work: AQUAMAN, a traditional superhero movie and THE FAVOURITE, where each of the three main characters have their own plot elements that line up with the hero’s journey.

Limitations of Three Act Structure

Three Act Structure was conceived during a time when theatre was the most popular form of entertainment. It then continued to be used in cinema. Theatre and cinema are both temporal: the story must progress over real time for the audience as there is a limit to how long we’ll sit still. But books are different. Every single reader consumes the story at a different rate, so these temporal constraints don’t exist.

Due to its genesis in theatre/cinema, the Three Act Structure focuses more on action with little emphasis on the interiority of characters, especially internal change. But since books allow for more introspection, your characters might undergo internal change in addition to their physical actions.

Finally, Three Act Structure is very broad: each act contains multiple chapters. A story isn’t actually divided into three parts; it’s an artificial divide. And if you plan the inciting incident and plot points as the only big twists and changes, you may end up with not much happening for most of the middle of your book.

Thinking broadly isn’t always the most effective way to draft or revise your manuscript. Maybe you need more detail? Or a different way of conceptualizing your story? That’s where a Four Act Structure can be useful.

Four Act Structure

A Four Act Structure breaks Act 2 at the midpoint, giving you four acts of roughly equal length. It’s easier for writers to wrangle, because it makes Act 2 smaller and more manageable and it highlights the importance of having some sort of structural midpoint, signalling a great reversal in the main character’s fortunes.

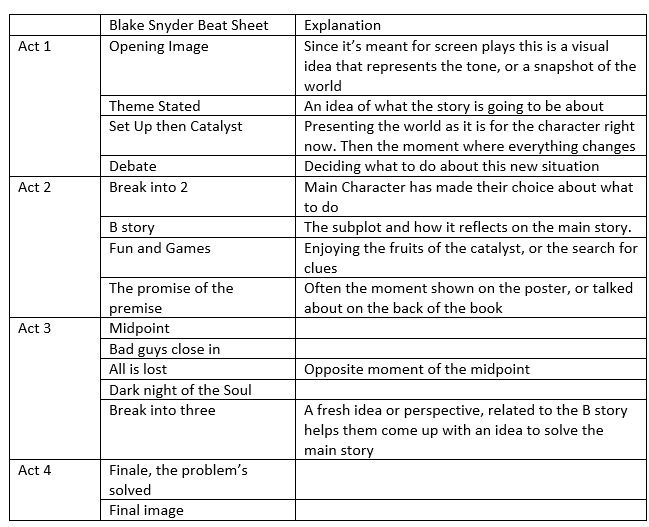

Blake Snyder’s book SAVE THE CAT outlines a 15-point structure that fits neatly into 4 Acts below:

Limitations of Four Act Structure

It has some of the same limitations of 3 Act Structure.

Additionally, The Save the Cat beat points focus on the big moments of a film; the ones that will be the talking points in the meeting with the producers or featured in the trailer. As such it can be reductive and should be viewed more as a baseline: your story should have these beats and it’d probably be a good idea if they occurred roughly at the same point in the narrative, but your story needn’t have only these points.

All stories will have some sort of structure, and Snyder argues they will all fit into his structure. Like, sure, I guess, you can squish your story to fit this exactly and have events occurring exactly on the page he says, but it won’t necessarily make it a better manuscript. Save The Cat works well when you use it as a starting point rather than a guideline that must be adhered to.

You can continue the Acts further, into five, six etc, but they still follow the principles of Three and Four Act structure.

Propp’s Functions

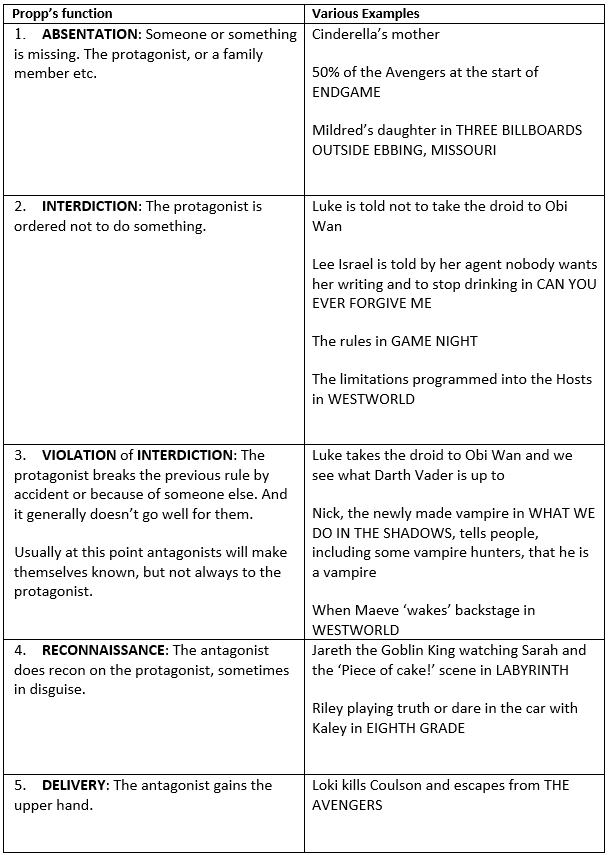

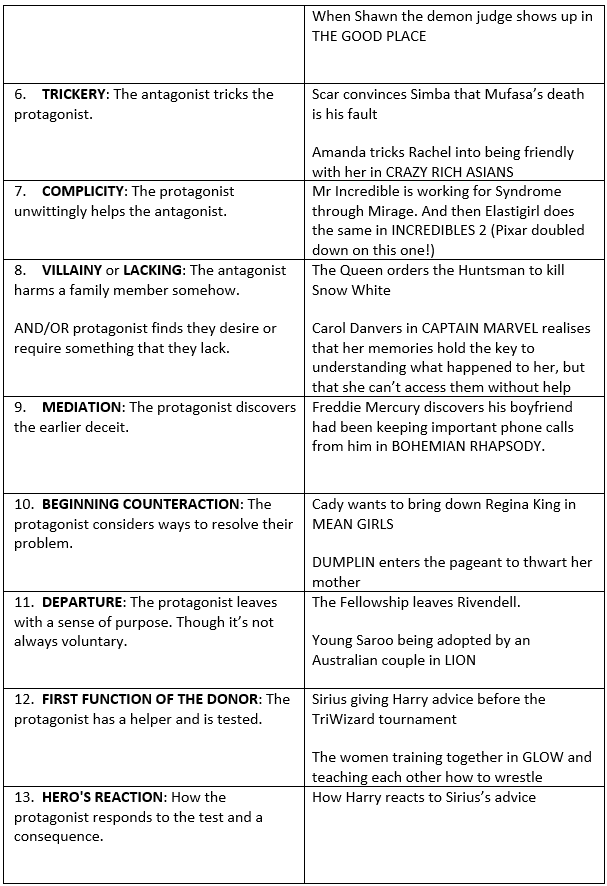

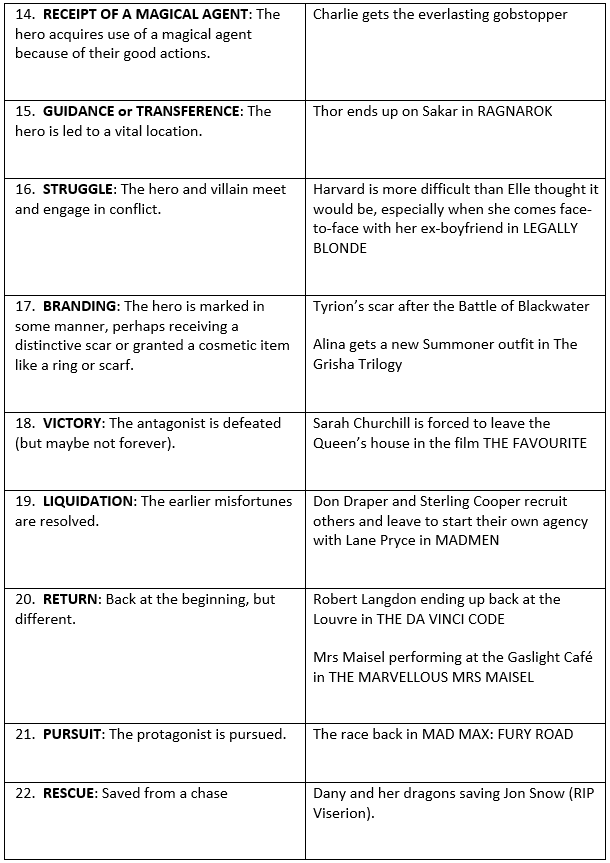

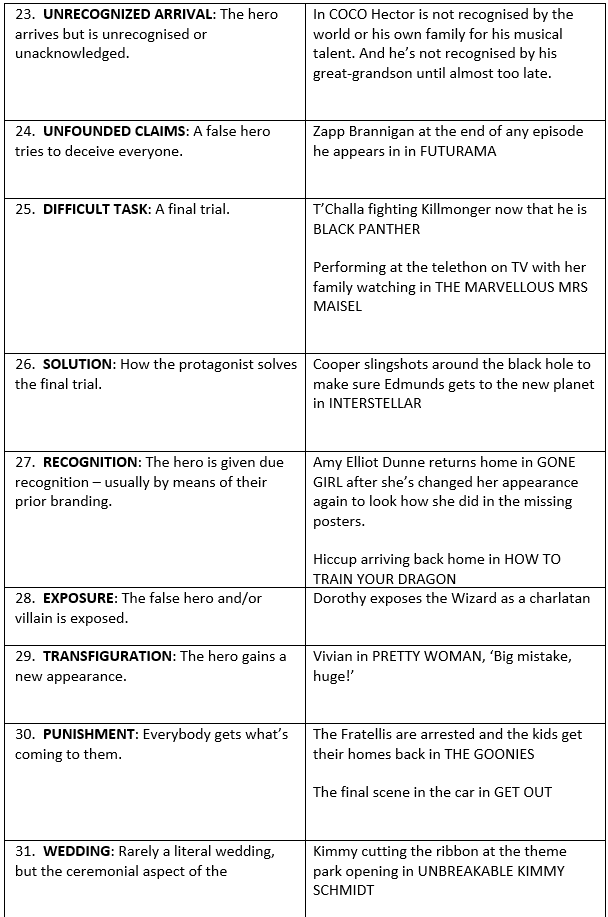

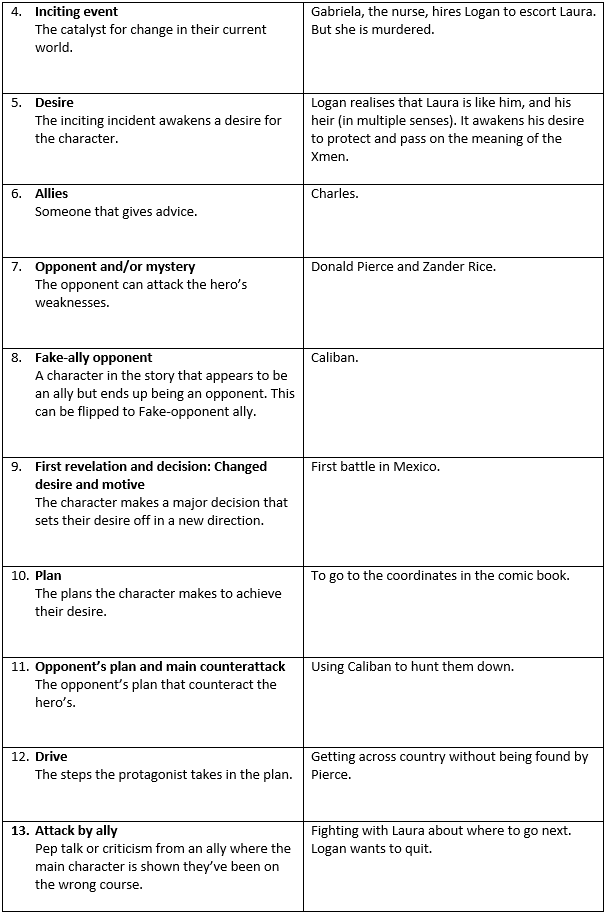

Propp was a fun Russian guy who analysed folktales for their most simple structural motifs. He identified 31 basic building blocks of story. He maintained a story didn’t have to have all 31 but that they had to be presented in chronological order (I disagree!). This is great for quests and fantasies but can be used in contemporary, as you’ll see. I’ve drawn from as many different genres and storytelling media as I could to show it does extend beyond the obvious fairy tale or quest.

As you can see, Propp’s functions are quite comprehensive. What’s important to note with the functions is that they include setups and payoffs, such as the villain deceiving the protagonist and then later that deception being discovered. They could be quite neatly divided into three or four acts as well!

The functions can also be subverted to make twists and surprises. For example, in THOR: RAGNAROK, Thor loses his hammer instead of gaining it.

Limitations

Again, it’s potentially formulaic. If you had 31 chapters and each chapter dealt with one of the functions, your reader is going to see any supposed twists a mile off. And, as I noted earlier, Propp believed the functions never appeared out of order. This may have applied to 19th-Century Russian fairy tales but there are now more areas for writers to explore and to mix it up.

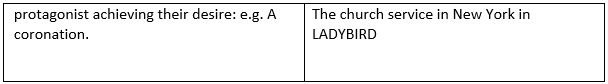

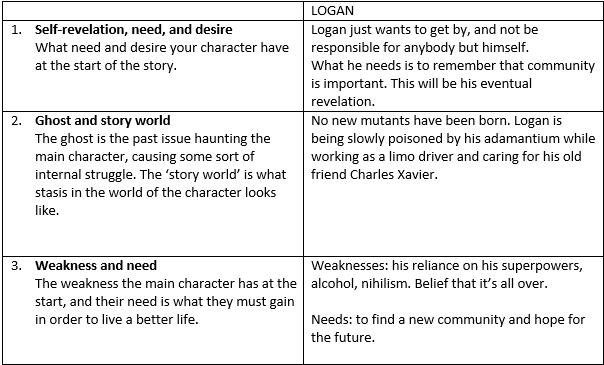

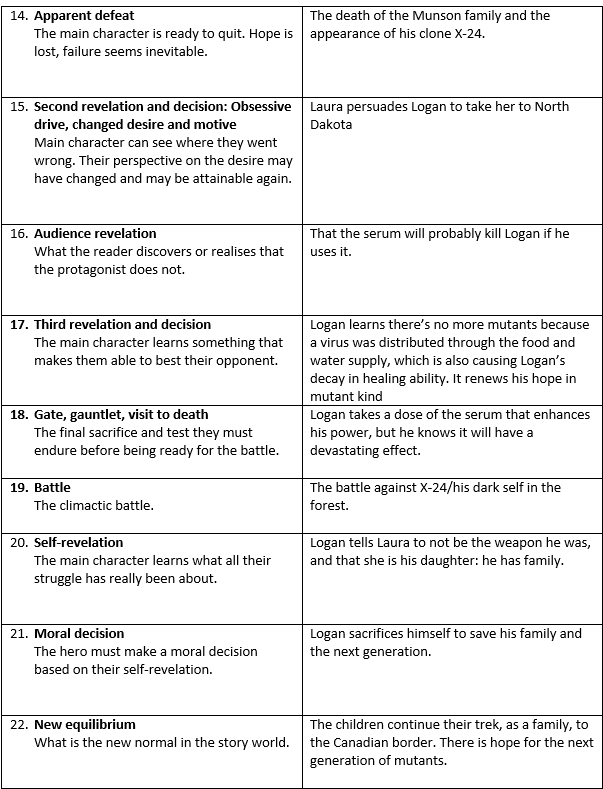

John Truby’s Twenty-two structure steps

John Truby is a screenwriter and teacher who defined the following 22 steps as the ‘backbone’ of story. As with Propp’s functions not every step needs to be in each story. Truby argues that it is more important to focus on the character’s needs vs their wants as driving the story rather than the external world forcing certain moments upon the character.

Limitations

Sometimes the Twenty -Two steps appear to be more abstract, as they don’t give any indication of what a scene might look like or what the action might be, versus the idea of ‘Approaching the Cave.’ It also requires a more in-depth understanding of your main character to plot out, as it focuses on their decisions and plans more than some of the other structures I’ve listed above.

Final word

There are more ways of thinking about structure, and there is a lot more depth to the structures I’ve discussed, and I’d encourage you to do further reading on the ones that appeal most to you. Whatever structure you choose for your manuscript, it’s meant as a map, suggestions for you how to not get lost! You don’t have to rigidly stick to any one structure. Because it is off the map is still where the discoveries are.

Over to you!

- Consider which story structure most closely resembles your WIP or which one appeals the most to you.

- Are you missing important plot points or functions? Consider the implications of not having them in the story.

- What are the major questions asked in each Act, and do they make sense?

- Look at how many of Propp’s functions you can identify in your story, and map where they occur in your story. What patterns can you see? Do you have some clustered close together or are they evenly spaced out? And consider the implications for your story. If you have stretches where there’s no identifiable plot element, does that mean that your story is not moving forward enough?

- Take a scene in your story that closely represents one of the functions and see how you can subvert it to make a new twist. Such as, instead of having the villain exposed as a charlatan, what if it was your hero that was exposed as a fraud somehow?

—

Cass Frances is an Australian writer who now lives in France. There, she is a manuscript assessor, slush pile reader and writer. She writes Young Adult fiction about ghosts, girls and goths, and anything else that exists at the slippery edges of reality. Cass has a Master of Creative Writing from the University of Melbourne.

Cass Frances is an Australian writer who now lives in France. There, she is a manuscript assessor, slush pile reader and writer. She writes Young Adult fiction about ghosts, girls and goths, and anything else that exists at the slippery edges of reality. Cass has a Master of Creative Writing from the University of Melbourne.

Reblogged this on unburntwitch.

LikeLiked by 1 person